It was Kick-Off Day minus 47. The wind howled around the empty, soulless Rush Green portacabins, as dust swirled across the cracked, abandoned car park. A single corner flag flapped rhythmically in the breeze, forgotten when the last training session ended just a few short weeks earlier. Nothing stirred except for an old man and the squeaking wheels of a white line marker in the far distance – otherwise, no life, no sound; only silence and despair.

In one corner, a rusty padlock hung above a door marked ‘Head of Recruitment’. A handwritten paper sign sellotaped to the splintered window read: ‘First Class Players Wanted – All Positions. Please state age, experience and preferred agent.’ Welcome to West Ham in the Transfer Window!

***

If You Can’t Convince Them, Confuse Them

A few weeks ago, I published an article on the realities of the financial situation at West Ham. Although, it is now accepted that West Ham had never faced an immediate threat of a PSR breach, the rules continue to be waved around as a portent for troubled times ahead – possibly the 2026/27 season but more probably the one after that. Yet in all likeihood, the existing PSR rules won’t survive that long now that Chelsea have destroyed their credibility.

Not surprisingly, it was in the Board’s interest to point the finger at ‘externally’ imposed rules rather than admit their own mismanagement for the club’s current woes. I had often wondered why the remaining Premier League clubs had voted for PSR in the first place given its major impact was to preserve the rich club status quo. But then you realise that for most, the priority is not to compete with the rich but to maintain their own advantage over those who are newly promoted.

The dilemma in understanding what is going on at West Ham in this age of misinformation is whether what we read has genuinely been leaked by the club, has been misunderstood/ misreported by the messengers or simply been made-up in the interest of internet clicks.

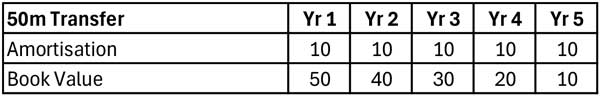

The major talking points in recent weeks have been the suggestion that only 75% of player sales will be made available for purchases, and the hint that a £90 million injection of capital is about to be made by the Board. The former is almost certainly a confusion arising from PSR accounting principles where only the excess of sale price over book value can be shown as player sale profit. I’m guessing that someone has made a back of an envelope calculation that this might equate approximately to 75%. As for the latter, the Board now find themselves in a position where they are obliged to invest further or face the prospect of PSR losses over the next three years being limited to £15 million, rather than £105 million. What form the investment takes, who puts their hands in their pockets, and how the money is used will provide interesting insights into the mindset and intentions of each of the owners.

Such is the dislike and distrust of David Sullivan by many supporters that is has spawned all manner of wacky conspiracy theories. Allegedly the Chairman has a secret plan to get the club relegated as a deliberate act of revenge, making a moonlight flit out of Stratford and baling out of an airplane over the nearest tax haven hugging his parachute payment. Personally, I believe the woeful management of the club is better expalined by Hanlon’s razor which suggests: “never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity.” For stupidity, read collective incompetence driven by a gaggle of overblown egos.

What A Waste of Money

It should come as no surprise to many that the effectiveness of West Ham’s transfer spending over the years has been atrocious. Take Declan Rice out the equation and the player trading profits are at the bottom of the league. If there was any lingering doubt, then take a look at the estimates of squad value calculated by the Transfermkt website (below). Not just that West Ham is ranked in 14th place – despite their relatively high spending – but how far they are behind clubs such as Brighton, Bournemouth and Forest.

1) Man City – €1.35 BN, 2) Chelsea – €1.21BN, 3) Liverpool – €1.09 BN, 4) Arsenal – €1.01BN, 5) Man United – €818 M, 6) Tottenham – €805 M, 7) Brighton – €732 M, 8) Newcastle – €597 M, 9) Aston Villa – €574 M, 10) Bournemouth – €466 M, 11) Nottingham Forest – €444 M, 12) Brentford – €432 M, 13) Crystal Palace – €426 M, 14) West Ham – €370 M, 15) Fulham – €318 M, 16) Wolves – €276 M, 17) Everton – €257 M, 18) Leeds – €211 M, 19) Burnley – €187 M, 20) Sunderland – €137 M

This is no accident or from run of bad luck but a direct consequence of failing to move with the times. Refusing to adopt a professional approach to scouting, recruiting and longer-term planning. Taking the easy option of relying on agents to identify targets rather than trusting the club’s own resources. Paying lip service to the trends of data analytics and appointing experienced football directors in the belief that a bunch of amateurs can do it better.

Profits on player sales is a significant component of football finances – and will continue to be important if/ when squad cost ratios replace PSR. A smarter club in West Ham’s position would have recognised this long ago and planned for the recruitment and development of younger players who can sustain and raise the club out of its current stagnation. It is a strategy that also calls for the setting aside of sentiment. There is an optimum time to sell any player, no matter who they are.

All Quiet On The Transfer Front

As usual the early days of a West Ham transfer window has been all noise and no action. Last summer I made of point of making a note of every player linked to the club but gave up after the list broke through the one hundred barrier.

The backdrop to this summer’s business have been the baffling public announcements of “we’re skint and must sell before we buy.” Quite why anyone would show all their cards before entering into any negotiations is beyond bizarre. Was the intention solely to manage supporter expectations, an attempt to hide behind PSR regulations or something more sinister. Now we know the club’s problem is cash flow (and not PSR), we also know that it is something the Board can quite easily fix – after all they broke it in the first place. The promised £90 million injection – in whatever form it takes – should serve to partially ease the impasse.

We know very little about the direction Graham Potter and Kyle Macaulay’s thoughts. The assumed principles of pursuing younger emerging talent sounds eminently sensible. Hopefully they are locked away in a quiet corner somewhere, methodically poring over the rows and columns of a recruitment spreadsheet. Keeping tabs on the players that the data has identified and preparing the bids to be put forward. But will they be allowed to excel themselves in the transfer window or will their preferred targets end up as more names in the list of the ones who got away? Sacrificed to the rubbish bin of low-ball bids, take-it-or-leave-it offers and DFS style payment terms.

Potter and Macaulay have a massive job on their hands to rebuild the Hammer’s sqaud. If they also to lose Kudus and Paqueta as predicted to fund recruitment the challenge becomes even greater – both in finding the players and subsequenting moulding a team from a bunch of strangers. My preference is that they are shopping in the under £25 to £30 million aisle, prioritising pace and excluding anyone aged 27 or over, except in exceptional circumstances. Otherwise, it will be a case of rinse and repeat when we reach the same time next year, requiring a third consecutive summer reconstruction.

Today, is when the majority of Premier League clubs get to close their accounts (West Ham’s closed at the end of May), so we can expect activity to pick up this week. There may also be last minutes manoeuvrings by any club (e.g. Aston Villa) who find themselves on the cusp of a PSR breach.

In truth, transfer business has been relatively slow across the board, but we have been here before at West Ham. Looking patiently at the clock as the minutes, hours and days tick by. When others start to spend while West Ham sit on their hands, making enquiries, considering targets and preparing talks.

As things stand the Hammers are deep in the ‘conversation’ for relegation. We cannot rely on there being three worse promoted teams again. We have to make ours better. It really is time to act. COYI!